Part 4 - Aftermath of the housing bubble

Part four of a nine-part series.

So far, we’ve looked at the factors that created the credit and housing bubbles and the beginning of their demise. As prices leveled off in 2007, speculators and borrowers who had subprime loans realized further appreciation was unlikely, so they simply stopped making payments and foreclosures rose. The possibility of this outcome appears to have been completely unforeseen by lenders because their models simply didn’t account for the fact that borrowers might default and, even worse, that those defaults might lead to losses. In August 2007, lenders woke up and removed from the market the majority of the more aggressive home-loan products that had propped up home prices.

Much of the blame for the nearly unprecedented fall in prices that followed the removal of those loan products has been placed on foreclosures. But that blame is largely misplaced. The reality is that prices fell because without the aggressive interest-only and payment-option adjustable-rate mortgage (ARM) loan products, very few people could afford to buy a home. Sales began to recover after prices dropped because buyers could once again afford to purchase a home, given their income and the loan products that remained available.

I want to be crystal clear on this point: Many people feel that borrowers were out of control, that they exhibited what Robert Shiller termed "irrational exuberance." I totally disagree. Buyers did what they have always done, which was to spend as much as their banker told them they could afford to buy a home. Skeptics may argue that borrowers should have known better. But let’s not forget that politicians, government officials, economists and financial industry leaders all claimed that there was no housing bubble and that it was a good time to “invest” in real estate. That's not to say there was no irrational exuberance--certainly there was--but rather, that it was politicians, officials, economists, regulators and investors, not borrowers, who were truly irrational.

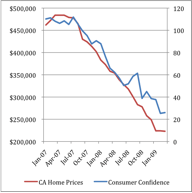

As home prices naturally plummeted to a level home buyers could afford, consumer confidence plummeted as well. See chart:

Note the fall in home prices occurs immediately after the loan products that enabled people to buy homes the twice the price they could really afford were removed from the market in August of 2007.

Unfortunately, the notion of a home as an investment, rather than a place to live and own outright during retirement, left most homeowners with the mistaken belief that this engineered home equity equaled net worth. Thus, as prices plummeted, so too did homeowners' sense of financial security. And since so many homeowners had tapped their home equity to live beyond their means, the drop in home prices also turned off a major source of consumers' purchasing power. Worst of all, many homeowners now owe more on their mortgage than their home is worth, so they're essentially trapped in a prison of debt with no ability to sell their home or refinance their mortgage.

Negative equity, I believe, is therefore the core problem. With 20 percent of US and 30 percent of Californian households with a mortgage now underwater, it is impossible to fathom how consumer confidence can return, or how the U.S. economy can begin to grow again, given that 65 percent of U.S. gross domestic product (GDP) comes from consumer spending.

How big is the negative equity problem? I put it at just under $4 trillion. I arrived at this estimate a couple of different ways, the simplest being based on the Flow of Funds data published by the Federal Reserve. According to the Fed, our nation's housing stock had a combined value of $11.8 trillion in 2000 with mortgage debt totaling $4.8 trillion. Compare that to the peak combined value of $21.9 trillion, an increase of 85 percent, in 2006 or the peak debt of $10.5 trillion, an increase of 117 percent, in 2007.

To be fair, incomes have risen 24 percent over that time and since price is a function of income and loan terms, it makes sense that prices should have risen a similar amount. Our housing stock is also about 11 percent larger. Taking these increases into consideration, combined values currently should be about $16.3 trillion, a loss of $5.6 trillion from the peak. Interestingly, Zillow recently estimated total housing losses to date at $6.1 trillion. To return to a housing market as healthy as the one we had in 2000 with a roughly 42 percent debt-to-value ratio (roughly one-third of homes are owned free and clear), mortgage debt should total around $6.8 trillion, which would require mortgage losses of around $3.7 trillion.

To put this analysis in perspective, I estimate we’ve seen around $250 billion in realized losses on foreclosed homes since this crisis began. I know we’ve had only $170 billion of loans foreclosed on so far in California, and the actual losses on those loans are far less than that amount since the eventual resale of the home recoups a portion of the loss.

Our financial system has nearly collapsed and yet we are only about 1/16 of the way through the core problem of negative equity. And let's be clear on another point: Neither home buyer tax credits, stimulus checks or loan modifications nor any of the other current efforts in Washington address this problem.